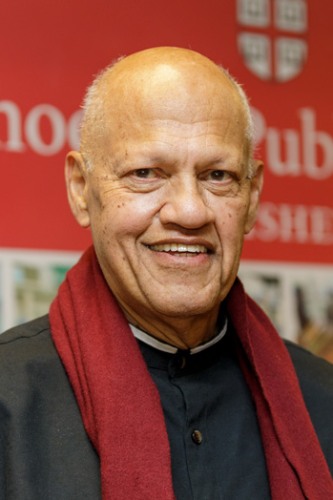

Wilmot James, Ph.D.

Biography

Dr. James, an internationally recognized thought leader in biosecurity, global health, and pandemic preparedness, is a Senior Advisor to the Pandemic and a Professor of the Practice of Health Services, Policy and Practice.

Dr. James has served as a Member of Parliament and Shadow Minister of Health in South Africa, and most recently held positions at Columbia University as Senior Research Scholar at the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy and as Chair of the Center for Pandemic Research in the College of Arts and Sciences. Wilmot serves as an advisor to the G7-led Global Partnership's Signature Initiative to Mitigate Biological Threats in Africa and on the boards of BEACON, Resolve to Save Lives and the Mirror Biology Dialogue Fund. Dr. James will use his extensive experience to address public health and national security challenges in his role as senior advisor to the Pandemic Center.

Recent News

Africa’s children are being failed by the hospitals they depend on — a wake-up call

---

Smarter Health Financing for Self-Reliance and Resilience Across the African Continent

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant slowdown in economic growth across Africa and triggered widespread debt distress, leaving many countries struggling to recover. Growth is expected to remain sluggish for several years, contributing to significant reductions in health spending. Official development assistance (ODA) has dropped 70 percent since 2021, even as disease outbreaks have surged by more than 40 percent between 2022 and 2024. These trends place overwhelming strain on health systems across the continent.

The combination of economic slowdown and reductions in ODA is unfolding in a time of increasing biological threats. Climate change disproportionately impacts African countries, driving a surge in infectious disease outbreaks across the continent. At the same time, rapid technological advances are lowering barriers to the misuse of biology. Yet many countries in the region lack the necessary data and core capacities to keep their populations and economies safe from emerging health crises.

AI bioweapons risk presents greatest challenge of our time — a surveillance state vs chaotic misuse

Remembering Nelson Mandela’s meeting with antiviral pioneer and Nobel laureate David Baltimore

---